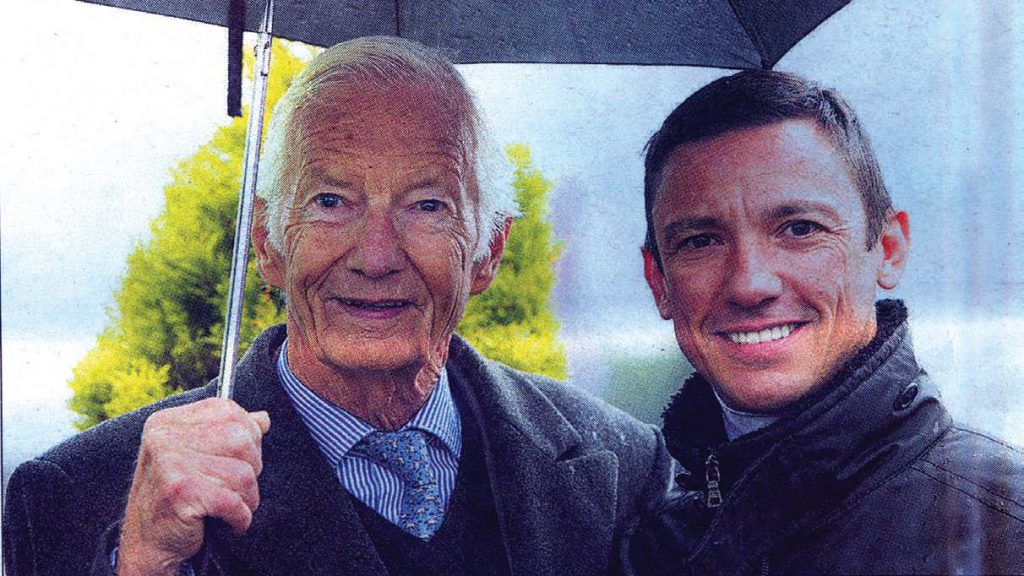

LESTER PIGGOTT

60 years ago a teenage prodigy changed the

60 years ago a teenage prodigy changed the

face of Derby history on Never Say Die

[dropcap]K[/dropcap]eith Piggott put the key in the ignition and started the car, ready for the drive from Lambourn to Epsom Downs. As he pulled away he glanced over his shoulder, saw the lawn needed a little attention and turned to his front-seat passenger. “Grass needs cutting Lester,” he said. Lester nodded his mind already at the end of the journey, already at the start of the Derby. “I’ll do it, Dad.”It was 60 years ago, Lester Piggott was 18, a quiet, understated individual but a firebrand of a jockey who would quickly reach the top of his profession and remain there for the rest of his career, bewitching generations with his unique blend of guile, strength, audacity, resolution and prodigious natural talent. On June 2, 1954 it all lay ahead of him, what little lay behind offered an augury of the way things would be.

He rode his first winner-The Chase, at Haydock, trained by his father, at the age of 12, aided in part by the rider of the runner-up urging him on as his own mount was “not off”. His progress was steady but sure, held benignly in check by his parents Keith and Iris, who had no intention of allowing their son to become affected by the increasing attention of the media.

Champion apprentice in 1950 and 1951, Piggott’s first major success came aboard Mystery in the 1951 Eclipse Stakes, by which time he had already had his first Derby ride on Zucchero, a talented but wilful animal who planted himself at the start and only consented to race once his chance had vanished. When asked later what he had learned from his first Derby ride Piggott, whose economical eloquence would be an enduring pleasure answered, “not to get left at the start”.

In the 1952 Derby he rode Gay Time into second place behind Tulyar and a year later partnered the unplaced Prince Charlemagne, a relatively undistinguished Flat performer who would the following year win the Triumph Hurdle at Hurst Park with Piggott in the saddle, the young man finding a way to make the most of his increasing weight before eventually subduing it under the manacle of superhuman self-restraint.

By this time he had efficiently become the darling of the punters and the bête noire of the authorities, on both counts for his indomitable will to win, which brought him suspensions and winners in seemingly equal measure. The Establishment was wary of him, the senior jockeys were resigned to being surpassed by him, and the racing public was enthralled by him.

So here he was, departing his father’s South Bank stables in Lambourn en route to Epsom as a young man of infinite promise, yet still only a young man, with his father at the wheel and his mother in the back seat, only a sketched-in canvas waiting for whatever came next to furnish the finished article. As the road unrolled before them he discussed tactics with his father, how best to maximise the chances of his long-shot mount.

The horse waiting for Piggott in the Epsom stables would merit his own footnote in Derby history beyond the bare details of the roll of honour. Never Say Die had been born in Kentucky and at that time no bluegrass-bred horse had won the race; here was a watershed moment in history, a case of après moi le deluge.

A son of the phenomenally pre-potent sire Nasrullah and the War Admiral mare Singing Grass, Never Say Die earned his name in the straw of a Lexington foaling barn, as vividly illustrated in James C. Nicholson’s book about the horse. It had not been an easy delivery-

Singing Grass was a slight mare and her colt foal was a hefty fellow- and the state of the newborn was a concern to the stud farm’s owner, John Bell.

Laughter is often said to be the best medicine, but bourbon whiskey is never far behind and Bell poured a good-size slug of it down the colt’s throat-after taking a swig himself-ofcourse. The liquor did the trick, its fiery properties provoking the spark of life, providing a most suitable name for a racehorse.

His owner-breeder Robert Stirling Clark, art collector, industrialist and heir to the Singer sewing machine fortunes- the ‘label’ tycoon was rarely so aptly applied-raced his horses exclusively in Britain, where he had won the 1000 Guineas and Oaks in 1939 with Galatea II, a half-sister to the dam of Singing Grass. Never Say Die crossed the Atlantic to join the Carlburg yard of Joe Lawson (trainer of Galatea II); Clark’s other British trainer Harry Peacock had first choice of the owner’s yearlings that year, but had little faith in Nasrullah stock.

The big chestnut colt with the white blaze and three white feet was no embryo superstar at two, winning just one race, a minor stakes event at Ascot, and finishing third in the Richmond and Dewhurst Stakes. Never Say Die’s Epsom preparation was ostensibly overwhelming; runner-up at Aintree in March; unplaced in the Free Handicap; third in the Newmarket Stakes; although it was here that the link with Piggott was forged.

“The Liverpool race was the first time I ever sat on Never Say Die. I liked the colt immediately. He was very straightforward, simplicity itself to ride. For that first outing he was far from wound up to full fitness and under the circumstances, did very well to finish second, beaten only a length.” Piggott rode the colt again in the Free Handicap, but preferred to ride at Bath, where he had three winners, justifying the decision, instead of maintaining the partnership in the Newmarket Stakes, where Manny Mercer took over. That third place at Newmarket over a mile and a quarter had endowed Never Say Die with Derby credentials, however scanty. He was 200-1 for the race until a superlative gallop the week before the race ensured odds began to tumble. But, at this time Piggott had yet to become the arch manipulator of owners and trainers with Classic contenders, yet to have the luxury of choice when it came to the biggest races.

Lawson, unimpressed by Piggott’s diversion to Bath, offered the Epsom ride to Mercer, but he was already booked for the 2000 Guineas winner Darius. Then Lawson turned to Charlie Smirke, but he was engaged to ride Elopement. Yet another rider was sought but to no avail. Lawson reconsidered his diminishing options and turned to Piggott, who accepted. One day Piggott would be the Housewives’ Choice; now he was no more than fourth choice and very glad of it.

Even so, at outsider odds of 33-1 Never Say Die was arguably still poor value for the Derby with just one victory in nine starts, and it was only his evocative name and exciting young jockey that made him relatively popular with the general public. His pedigree however, indicated stamina, as did his improved showing at Newmarket last time out, and Piggott went armed with more than just the unbridled enthusiasm of youth.

“I was expecting a major improvement on his previous efforts,” Piggott said. “I discussed with my father the best way to approach the race from a tactical point of view and we agreed that the best horse to track would be Darius. He was clearly a horse with some class, although there were questions about his stamina.”

There were 22 runners on the chilly, overcast Wednesday afternoon, with the market led by 5-1 joint favourites Ferriol , runner-up in the 2000 Guineas, and Lingfield Derby Trial winner Rowston Manor. Then was the aforementioned Darius and Elopement, the only four at a single figure price. It was a very open Derby, fertile ground for something to seize the day and call it its own.

“In many ways Never Say Die was the ideal Derby horse-physically compact and very well balanced, temperamentally equipped to put up with all the distractions of the long drawn out preliminaries,” Piggott noted. “I was able to ride the race exactly as I wanted.”

Clark, 78 was at Epsom, having book a stay at a health farm, possible through lack of confidence in his homebred’s chance. Piggott, clad in Clark’s gaudy cerise and silver stripes with a blue sash, and the 73-year-old Lawson, stood together in the parade ring as the horses circled. It is unlikely that many words were exchanged before Piggott was lifted into the saddle amidst the traditional and now largely absent bedlam of Derby Day.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n later years Piggott held on to a highly successful pattern in the Derby-the highest backside in the race was often seen to be perched in 5th or 6th place away from the rail on the descent to Tattenham Corner, just behind the front rank, ready to pounce at precisely the right moment. That pattern began to emerge on Never Say Die. We should allow the great man to condense that helter-skelter two and a half minutes in his own spare style.

“Never Say Die sat behind the leaders throughout the early stages, came down the hill smoothly, and at Tattenham Corner was perfectly place in fifth on the outside behind Rowston Manor, Landau, Darius and Blue Sail,” he recalled. “Once into the straight, Blue Sail weakened and fell back, and neither Rowston Manor or Landau could hold their positions for long, and I eased Never Say Die forward as Darius took the lead with a quarter of a mile to go. Never Say Die was going so well that he swept past Darius in a matter of strides and after that I allowed myself the luxury of a quick look round to check that nothing was catching me from behind and, that was that.”

That was that. The statisticians record that fellow 33-1 shot Arabian Night was runner-up, two lengths away, with Darius a neck back in third and Elopement in fourth. In his pomp, Piggott’s face was described as having ‘all the emotional output of a well-kept grave,’ but at 18, the second youngest jockey ever to win the Derby, only outstripped in his way by the stripling John Parsons, who was apparently 16 when riding Caractacus in 1862. Old Stoneface was but young and in a photograph is clearly smiling widely as he is led into the winner’s enclosure. Lest we should get carried away, though, Piggott was quoted the next day as describing his breakthrough success, “as just another race.”

“The race could hardly have been simpler, which perhaps accounts for my lack of visible ecstasy as we passed the post,” Piggott later wrote, and it is probably fair to say that Piggott would be more likely to stand drinks for everyone at Epsom than to do a ‘Barzalona’. “The fact is that never at any point of time in my career did I allow myself to appear overjoyed after winning a race, big or small, and however much the press demanded it, I could not and would not manufacture elation. Never Say Die’s Derby victory gave me the satisfaction of job well and properly done, but that was all.”

The newspapermen did the job for him, soaring to poetic heights to fully embrace this thrilling charging of the guard, this fresh ace in the pack. The Daily Mail called him ‘a brilliant boy,’ the Daily Mirror described his ‘unhurried authority’ and his ‘brilliant meteor-like rise to riding fame’. But for Piggott, the greatest day of his career thus far tended more to the prosaic, to the calm contentment of that, ‘job well and properly done’. He later won the last race of the day and then his parents drove him home.

Never Say Die was retired to stud at the National Stud , where he sired his own Derby winner in Larkspur; Clark died two years later; Lawson in 1964, by then a member of the exclusive band of trainers who had won all five Classics. For Piggott, of course, there would be eight more Derby winners, and more than 5000 victories in a two-phase career of irreducible glory that drew to a subdued conclusion in 1994. All that was still to come; the names of Crepello, St. Paddy, Sir Ivor, Nijinsky, Roberto, Empery, The Minstrel and Teenoso still to take their places in the story of the greatest Derby jockey ever.

But if the 18-year-old Piggott considered the future at all, he kept it to himself. There was something else on his mind, something more immediate. There would be no great celebrations; when Lester got home. He mowed the lawn, as he said he would, and was in bed shortly after nine.

An ordinary day…an extraordinary day.

— Steve Dennis

Courtesy-The Racing post

Published in Racing World India Printed Magazine August-September 2014 Issue.