Developments in the Indian breeding industry

Will the recent trend in imports improve the Indian-bred?

— Anil Mukhi

Many racegoers in India rarely stop to think where the horse – on which they are risking their ten rupees in a race – comes from. Every thoroughbred horse currently racing under rules anywhere in the country is the product of a long chain of events that commences with the acquisition of “foundation stock”. The old dictum “As you sow, so shall you reap” has never been truer than with horses, and unless one starts with stock of a certain standard, there is little or no chance of producing a good racehorse. This is why quality stock needs to be imported continuously to replenish the ranks.

Organised horse racing in India has a long history, extending back to almost 250 years. Initially, racing was conducted with a few ready-made imported horses, chiefly sourced from England and Ireland, as also with the so-called “country-breds”, a somewhat derogatory term used by the then rulers of India to describe local horses of unknown provenance. An owner in the 19th century, in search of a new horse of some quality – perhaps to replace one that was retired due to normal wear and tear – had necessarily to source it from abroad. Due to the long voyage involved and economic conditions of the era, the numbers so imported from the British Isles during that era were limited.

By the early part of the 20th century, Thoroughbreds began to be imported on a significant scale. Meanwhile the initial Indian stud farms, such as the Kunigal Stud, the Royal Stud (now the Manjri Horse Breeders Farm) and the Renala Stud, began producing Thoroughbred racehorses. The Army established Remount and Breeding stations, using imported stallions for stud purposes, and Thoroughbred breeding in India finally began to take shape as a significant industry. The National Horse Breeding and Show Society of India published the first (unofficial) version of the Indian Stud Book in the ‘thirties.

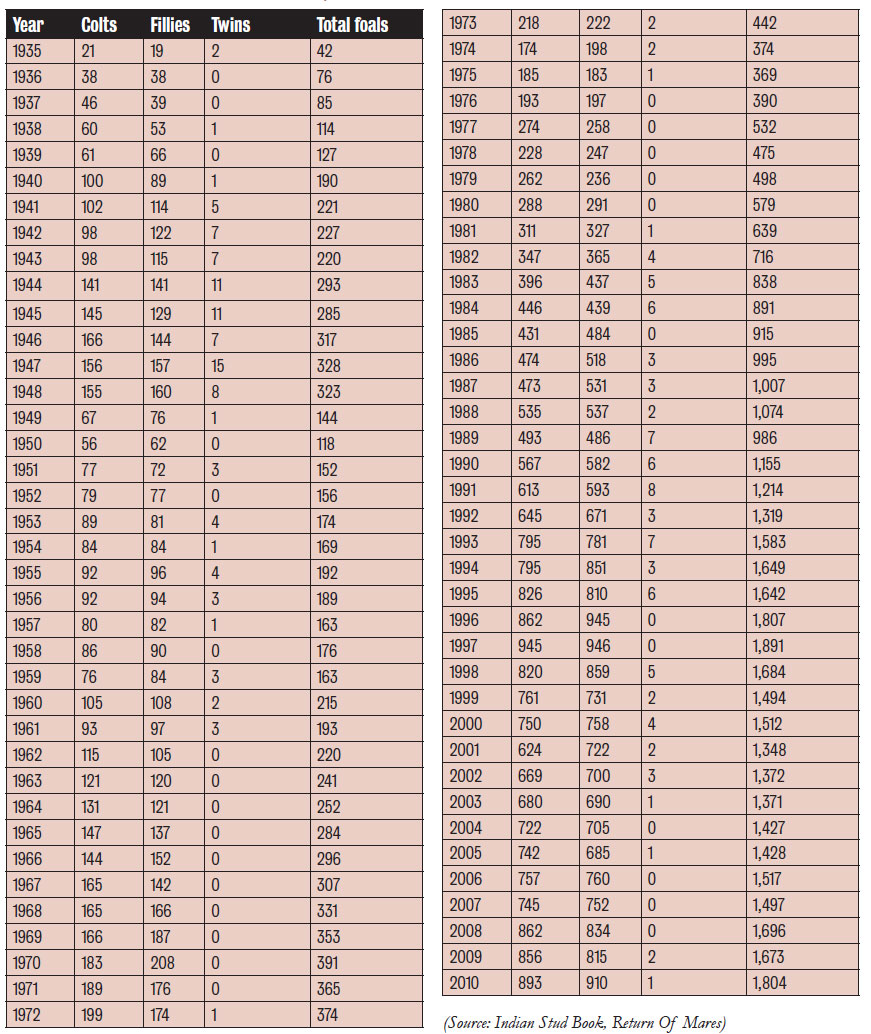

During the second quarter of the century, the official Indian Stud Book was published, Volume 1 making its appearance in 1942. From just 42 Thoroughbred foals of indigenous production added to the racing population in 1938 (foals of 1935), the number rose to 227 by the mid ‘forties. The advent of the Second World War saw a substantial reduction in the broodmare strength in Europe, and many of the mares so disposed of by studs in that continent ended up in India, leading to an even further increase in the number of foals bred here – production peaked at 328 in 1947.

Table 1 below gives the production details from 1935 to 2010.

ANNUAL FOAL CROP IN INDIA, 1935- 2010

Of course, the unfortunate Partition of the country saw the foal crops being divided between India and the newly-formed country of Pakistan. This was something the industry could shrug off as a once-in-a-lifetime event. What proved galling though, was the post-Independence attempt by conservative politicians to close down racing, a move which threatened the very existence of the Indian Turf. Not surprisingly, foal production plummeted, reaching its nadir in 1950, when a mere 118 foals were registered. As one can imagine, the mood at the time was exceedingly grim.

Intensive lobbying rescued the situation. Once the threat was past, the breeding industry in India slowly recovered, the 192 foals of 1955 representing a smart 63% increase in five years. It was not always smooth sailing, though. A shortage of foreign exchange in 1958 led to the introduction of import licensing which in turn led to a severe fall in imports (as an aside, import licensing, which ought to have been abolished a decade or two ago, continues to be a scourge affecting breeders). The combination of a sluggish economy, abolition of the tax benefits from horse breeding, and import restrictions meant that it took till 1968 for the 328 mark, first set in 1947, to be scaled once again!

Gradual loosening of economic shackles saw the breeding industry registering smart gains in subsequent years, including a doubling of production in the 7 years between 1979 and 1986. With more races framed each year, production soared in the ‘nineties, to record another peak in 1997, when 1,891 foals were bred in the country. However, the experiences gained during the period 1993-1998, when the crop exceeded 1,500 in each year, demonstrated that anything significantly north of that number amounted to over-production. Prices accordingly suffered during this time.

A disciplined period of almost a decade brought remarkable stability in the marketplace, with production hovering around 1,400-1,500 foals annually. There were stables at the racecourses for all. However, with no new tracks having been established since 1947, and with exports hampered by bureaucracy, logistical issues and lack of foresight, the 1,500 mark currently represents a ceiling over which breeders venture at their peril!

The last four years have seen an unbridled expansion in production, which is sure to affect margins, and which can only be rectified in the short term by culling perhaps as many as 500 low-quality broodmares. There are calls to restrict imports to save the day. Unfortunately, it is not 50 or 100 additional broodmares (over and above the number normally imported as replacements) that pose the problem. It is the way the system is structured. The true culprits are:

a) absence of a realistic auction medium

b) lack of two-way trade

c) restrictions on foreign-bred runners

d) emphasis on quantity over quality

e) failure of any new racecourse project to materialize

in post-Independence India

Absence of a realistic auction medium

The auction medium for youngstock has been effectively killed by the race clubs that conducted such sales. The Madras Race Club discontinued its sales while the RWITC Ltd. started levying usurious entry fees, thereby converting the sale from one which invariably drew a galaxy of buyers to one where principally “left-overs” are traded (although the occasional good horse can still be found). And there are no breeding stock auction sales.

Thus real sales of yearlings take place at stud farms all over the country. Every breeder needs to have one or more star lots to attract trainers (the principal buyers) to her or his farm. So she or he wants a “got-abroad”, which means importing a broodmare, whether or not there is need for one or even the space to house it. The absence of realistic auction sales is an anomaly that needs swift rectification.

Lack of two-way trade

The closed nature of Indian racing, with classics and several major races restricted to Indian-breds, prevents the country from being taken seriously in international circles, and hampers exports. New Zealand – with a GDP about one-eleventh that of India’s – produces thrice as many Thoroughbreds annually and exports about as many each year as India breeds in the same period! Open trade would ensure broodmares left India as well, instead of coming in on “one-way tickets”…. And any hypothetical over-production of youngstock could be absorbed by exporting pre-trained runners to neighbouring markets.

Restrictions on foreign-bred runners

Were foreign-breds to be permitted to run in classics and major races in India, there would be no need to import their dams that end up “polluting” the stud farms and producing additional foals in subsequent years which no one wants. There are reports of entities importing large numbers of broodmares (like 30 at a time), with a view to taking the harvest of “got-abroads” before parting with their interest in these broodmares. Nothing wrong with that as a business model – except that the broodmares appear to have been selected more for the calibre of the covering sire (high) rather than their own intrinsic qualities (low) – and now there will be 20 foals in 2012 out of this bulk lot alone.

Removing the “Indian-bred” restrictions, which have outlived their utility, would enable breeders to import weanlings or yearlings instead. And before anyone claims that this would be the “death of Indian breeding”, let it be pointed out that only those who produce uncompetitive rubbish will be affected.

Would the Indian public prefer that the era of Ambassadors or Premier Padminis had been extended by artificial restrictions? Remember, in the ‘seventies there were just 50,000 poor quality motor cars produced per year, and exports were virtually nil… Opening up the auto sector has resulted in annual production exceeding 2,000,000 passenger cars with exports of around 500,000 units. With vision, a similar boom can take place in the Indian racehorse business.

Another ready comparison of the potentially deleterious effects of xenophobia is at hand – would legends like Sachin Tendulkar and Rahul Dravid have been legends of cricket if they had been – and here I am choosing my words carefully – restricted to playing against local bowlers in Indian conditions only? No, it is intense international competition that has honed their talents and made them stars. Indian racehorses need such competition. Let’s not forget that till the ‘seventies, there were several imported runners on Indian tracks and the Indian breeding industry did not close down then!

Emphasis on quantity over quality

So far this piece has focused entirely on the aspect of quantity. After all, it’s easy to wave a catalogue and buy a broodmare at an international sale, and apparently a lot of hand-waving has been going on. A random survey of broodmare imports to India suggests that as many as 50% are unperformed!

Quality is more elusive. The emphasis on numbers displayed so far ought to change – something which Japan realized a few years ago. According to the JBBBBA website:

“Thoroughbred breeding in Japan began in earnest after the end of World War II in 1946, and in the early 1960s, the number of horses produced each year finally reached 1,000. During the 1960s these figures climbed from 2,000 to 3,000, continuing thereafter, until rising to 10,000 in the early 1990s.

However, after this, the breeding industry changed its policy and began focusing on the quality of horses, rather than simply increasing the numbers produced. This saw the number of foals produced, drop into the 8,000s. It remained around this level for several years. Since peaking at 8,807 in 2001, the number of foals produced has been declining slightly each year”.

In fact there have been nine straight years of declines in numbers in the “Land of the Rising Sun”, with the 2010 figure being down to 7,112. Note that Japan imports no more than 2 or 3 stallions annually – and when they do, the horses are Epsom Derby winners or equivalent. India imports around 10-12 stallions each year, more than half of which ultimately prove to be “pea-shooters”, not “cannons”. Note also that Japanese horses are competitive in races like the Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, while Indian horses are hard pressed to win a handicap in Mauritius!

In fact there have been nine straight years of declines in numbers in the “Land of the Rising Sun”, with the 2010 figure being down to 7,112. Note that Japan imports no more than 2 or 3 stallions annually – and when they do, the horses are Epsom Derby winners or equivalent. India imports around 10-12 stallions each year, more than half of which ultimately prove to be “pea-shooters”, not “cannons”. Note also that Japanese horses are competitive in races like the Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, while Indian horses are hard pressed to win a handicap in Mauritius!

Failure of any new racecourse project to materialize in post-Independence India Establishing new racecourses is a vexed  issue, a study of which is beyond the scope of this piece. It bears mention, though, that the laudable move on the part of the Government of Punjab to set up a racecourse in that state is fairly advanced and needs to be encouraged. This could provide a short-term “quick-fix”, even though the structural problems outlined above will still remain.

issue, a study of which is beyond the scope of this piece. It bears mention, though, that the laudable move on the part of the Government of Punjab to set up a racecourse in that state is fairly advanced and needs to be encouraged. This could provide a short-term “quick-fix”, even though the structural problems outlined above will still remain.

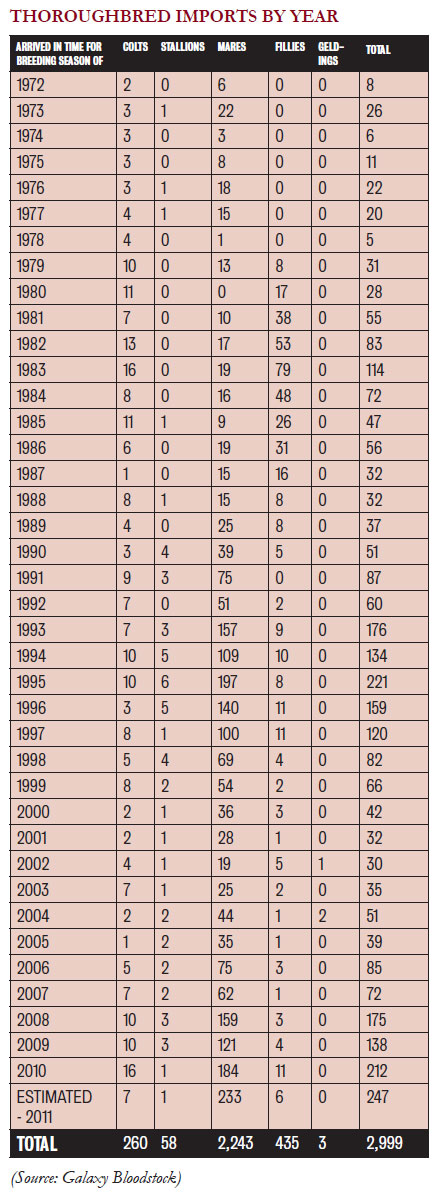

Table 2 below shows how the breeders who import react to events in a cyclical manner. During the past 40 years, or roughly 4 generations, there have been three peaks (1983, 1995 and 2011), when the ugly threat of over-production has forced subsequent cutbacks. The 2011 foal crop, exact figures for which are not yet available, promises to be the largest ever in India’s Thoroughbred breeding history and its size is likely to be the trigger for a fall in numbers of Indian-breds over the next half a dozen years.

It’s not all gloom and doom, though, as a shift in focus to quality, and implementation of the reforms outlined above, will certainly raise the profile of the Indian-bred to international standards. The industry needs to import more broodmares like Kalpita (whose son California Memory won a Gr.1 this year and has earned about US$1,000,000), Personal Allure (dam of Turallure, like California Memory a Gr.1 winner in 2011 and million-dollar earner), Sun Shower (dam of recent Gr.1 winner Excelebration), Final Refrain (young performed racemare in foal to a champion) and Khalila (young performed racemare in foal to a proven sire) – and less crocks and proven abject failures.

A simple shift in customs duty on broodmares from the current 36.136% ad valorem duty to a fixed specific duty, as in Japan, would hasten this trend in short order.

October-November 2011