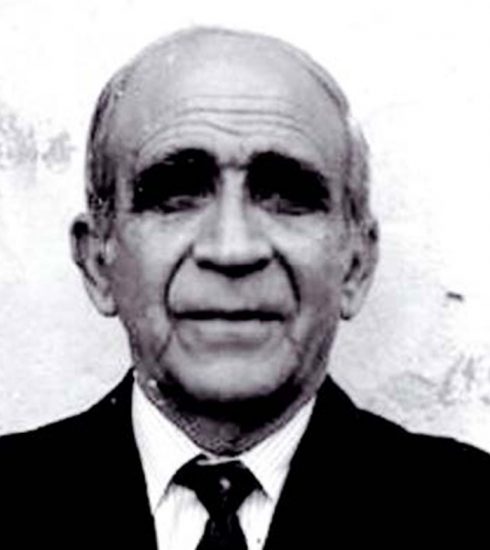

FACE TO FACE WITH A LEGEND: Vincent O’Brien

‘Of all the Derbys, the one that got away brought the heartiest chuckle.’

Brough Scott visited the legendary trainer whose six Derby winners helped him set the measure of greatness.

He was in a wheelchair as we saluted him as this year’s guest of honour and he didn’t talk a lot. But he had a deep sense both of the Derby’s history and of his own at Epsom. It’s important that we do too.

Meeting Vincent O’Brien in his London flat was a mixture of pleasure and awe. The smile is a bit crumpled now, but neither the years – he was 91 in April – nor the travel – his wife Jacqueline flew in from Perth – can block the kindness out. It is great to see them. Their son Charles’s wife Tammy is with them as is Johhny Brabston, whose namesake father was the gallops partner of Sir Ivor, Nijinsky and all the rest. Ah yes, here comes history on the hoof.

For here, chuckling gently at some of our sillier memories, sits the man whose presence has transformed the way we look not just at the Derby, but at the whole international racing scene. There might be something timeless about the view across Cadogan Gardens towards Knightsbridge, but it’s not possible to visit Vincent and avoid the time machine and the rigours within.

His very first Derby runner takes us back to 1957, with Ballymoss finishing second to Crepello and a 21-year-old Lester Piggot. Ballymoss was to subsequently take the Irish Derby, the St. Leger, the Eclipse and the Arc de Triomphe. In Flat racing terms he was the beginning of greatness. But his 40-year-old trainer was already a legend at the other game, having saddled his third consecutive Grand National winner in 1955, a unique feat he had also achieved in the Gold Cup and the Champion Hurdle.

Last week, Vincent would only give that trademark modest dip of the head when reminded of the hassles along the way. But to really appreciate the six Derby winners that followed Ballymoss’s effort, you need to understand something of the O’Brien journey. How he had to bet at the beginning. How his pioneering success bred envy as well as admiration. How, in 1953, the Irish stewards warned him off for three months for ‘inconsistencies in form’ that could have been explained by the thickest punter. How, in 1960, they put him off for 18 months for a preposterously botched doping allegation regarding subsequent Irish Derby winner Chamour, only reduced to a year by Vincent taking those stewards to the court of libel.

No wonder he was not best pleased when the first thing the English stewards did after Larkspur had won the seven-horse pile-up Derby on 1962 was to have Vincent in to explain the betting patterns around his winner.

“It was ridiculous,” says Jacqueline. “Larkspur had a swollen leg and so we told everyone he might not run, but when the odds drifted his owner Raymond Guest went and backed him because he loved a bet. The stewards accepted it, but Vincent had his hat stolen and I could not help, because I was trying to explain to the owners of our other horse Sebring why Raymond was in the winner’s enclosure and not them.”

It was in the spring of 1951 that Jacqueline Wittenoom, the 22-year-old daughter of an Australian MP, journeyed up to Europe on an economics scholarship, and when she reached Dublin, Vincent reached her. For all his public reticence, a central part of Vincent’s genius is the ability to see the future and act on it. However well that served him in racing, nothing ever matched the dividends he got from Jacqueline. And we are not just talking about their children.

For Jacqueline was the perfect foil: bright, vivacious, organised and fiercely loyal. One early-morning Epsom savaging of an increasingly hapless John McCririck would have had the referee intervening, except that Jacqueline and we spectators all had such smiles on our faces. Then and now she was Vincent’s rock – and talking to them last Wednesday was to remember how rocky a passage each Derby was.

Ballymoss ran terribly first time out as a three-year-old and then bruised a foot. Larkspur had looked so lame as to be declared a doubtful runner. Larkspur had looked so lame as to be declared a doubtful runner. Sir Ivor went to Pisa for the winter and one morning got loose, and but for Vincent and Johnny Brabston would be missing in Italy still. Nijinsky, already hailed Horse of the Century, had colic on Derby eve, Roberto had Piggot replacing Bill Williamson the day before. The Minstrel had cotton wool stuffed in his ears to get through the parade and a young and big-hatted John Gosden down at the start to take it out. Golden Fleece looked so big and sweaty and lumbering cantering down that my co-commentator Piggotmuttered the immortal verdict “don’t like that much”.

And that is before we get to El Gran Senor. Of all the Derbys, the one that got away in 1984 brought the heartiest chuckle and deepest sigh. After the Guineas, Vincent was for once happy to be quoted that his colt might prove to be the best, and indeed the most valuable, he had ever trained. With a furlong to go at Epsom he looked certain of it, only for his sons David’s Secreto to snatch it away at the line.

“The money simply does not matter,” he said to me on an ITV interview stand, “I am just absolutely thrilled for my son.” In the billion-dollar bloodstock world there is almost as much spin as in Number 10. But that was from the heart.

When you think of Vincent O’Brien and the Derby, it is not spin but wonder. He revolutionised training, bloodstock lines, and indeed the link with America, of which Ballymoss’s owner John McShain was his very first example. Looking back, his career might seem set in the stars, but it did not feel like that back then any more than when Dry Bob and Good Days had to win both legs of the 1944 Irish Autumn Double to get him off the ground. Ballymoss was only meant to winter at Ballydoyle as a yearling before going to race in America. But Vincent wrote beautiful letters to McShain about “the Mossborough colt” and even took the liberty of entering the horse in the Derby.

McShain was a hard and clever case, but was no match for the original maestro from Ballydoyle. “Yet it was worth all the trouble, wasn’t it darling?” Jacqueline said last week. Vincent took his time to get words and breath together, but then you could hear again that carefully modulated voice with all the pride of the years flooding through. “It . . . certainly . . . was,” he said.

Vincent O’Brien has set the measure of greatness. You will understand why there was awe as well as pleasure in that London flat on Wednesday.

Legendary frame: Vincent O’Brien with the great Lester Piggot

Legendary frame: Vincent O’Brien with the great Lester Piggot

Taken from Racing Post, UK daily

AUGUST – SEPTEMBER 2008 ![]()